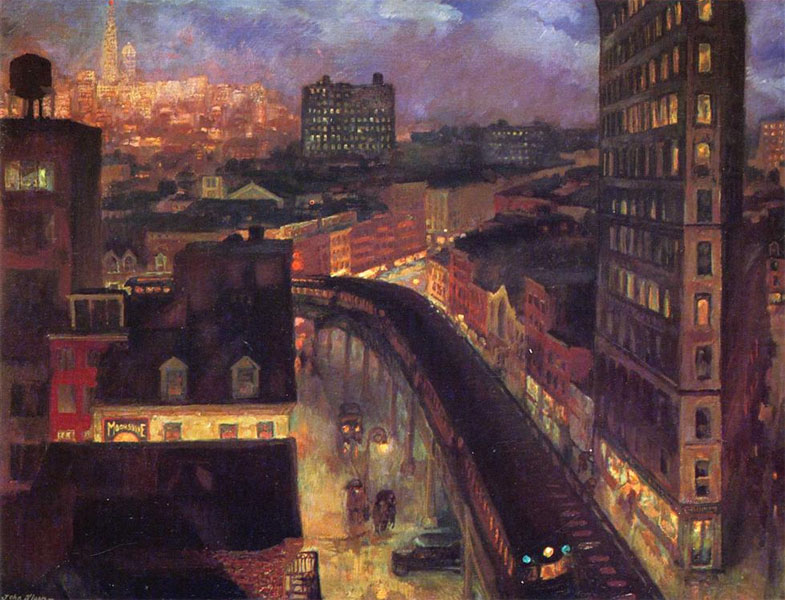

| ....and, perhaps

his best known work, "The City from Greenwich Village, 1922":

The City from Greenwich Village

Years later, I, too, would be

walking on the

streets of New York, especially in my native borough, the Bronx, but

instead

of seeing people and objects as an artist would--to know and be just

to--I

would usually be "in myself," hardly noticing what was around me.

In The Right of, #1291, titled "More Life," Aesthetic Realism Chairman of Education Ellen Reiss asks,

Who is more

alive:...a person who

can look at an object, maybe the bare branch of a winter tree, and be

interested

in it, feel that in its humble bareness yet proud diagonal lift it is

beautiful?;

or...a person who looks at the branch yet doesn't really notice it, and

moves on?

Most of the time, I moved on. I

felt the only

thing interesting and exciting were sports, and I often imagined myself

the star with people applauding me, first as a player and later as a

sports

reporter on radio. I felt people who got all worked up about

beauty--flowers,

trees, art of any kind--were just foolish and wasting their time. I

would

scornfully think, "I don't need that, it doesn't put any money in my

pocket."

As a

boy I was constantly

after my father and older brother to take me to Yankee Stadium, The

Polo

Grounds and Madison Square Garden. l didn't know it, but the

reason

I loved sports is explained by the great Aesthetic Realism principle,

"All

beauty is a making one of opposites and the making one of opposites is

what we are going after in ourselves." Sports puts together

opposites

such as mind and body, surface and depth, individuality and

relation.

These opposites were in the greatest hitter I ever saw, the Red Sox'

Ted

Williams, who, along with unique physical ability, carefully studied

the

art of hitting, and then generously wanted to help other players,

including

giving hitting advice to members of opposing teams. I needed to

put

these opposites together in my life--to be deeply interested in other

things

and people as the means of being my individual self.

Not

knowing this,

I went for the pleasure of making less of things, building myself up at

the expense of other people, who, I assumed, I didn't need to be

interested

in or affected by. When I was about 9 or 10 years old and guests came

to

our house, I felt very uncomfortable and often would go to another room

preferring to listen to the radio. When my parents wanted to

visit

relatives or friends, I would make their lives miserable by either

refusing

to go or by finally going reluctantly. I would think, "Who needs

this? I don't want to be with those boring people." While I gave the

appearance

that I was quiet and shy, inside I was a snob, feeling nobody else had

a life really worth thinking about, or that they, in any way, could add

to me. This ugly desire to ward off and lessen others literally made me

less. I felt hollow and lonely and I thought this was how I would

always be.

In one of the first classes I

had the honor

to attend in 1972, taught by Eli Siegel, he asked me:

In the field of

ethics is there anything

compulsory? In the field of art is there anything compulsory?....Is

there

a need to do the best with yourself as you can? Do you think there is

something

that impels one to hope one has had a good effect?

I had no idea such a hope was in

me. Mr. Siegel

then asked:

Do you think you

would feel bad if

you felt you had a bad effect on anyone?

MP. Yes. I think I had a bad

effect on my

parents.

ES. Where do you think you

hurt them?

MP. I could have been

kinder.

ES. Do you like to encourage

people? Do you

think if you failed to encourage people you would feel bad? The chief

thing

we are concerned with is what we might have done that we didn't

do....There

is an imperative to think as well of ourselves as we can.

Studying

what Mr. Siegel

called "the ethical imperative" gave me a new purpose. It changed

the dulling, life-sapping course of my life. Shortly after this class,

I met with my father, who was visiting from Florida, and we had the

first

real conversation we ever had. I actually asked him questions

about his

life, feeling I needed to know and be fair to him. I told him what I

was

learning newly about myself, the regrets I had about my meanness to him

and my mother. As we talked, I saw that I had missed so many

things

about him. He told me about his childhood on the lower east side

and how he saw his father, who had sold second-hand clothes in a cart

to

support his family. We were both very moved, and he was impelled

to write to Mr. Siegel that day, thanking him for the effect Aesthetic

Realism had on my life. He wrote, "I feel this one day added

twenty

years to my life." I feel greatly fortunate for my rich, happy life,

which

includes my marriage to Lynette

Abel,

whose keen, lively seeing of the world, her passion that justice come

to

other people encourages me every day.

continued

on page 2

|