Aesthetic

Realism

seminar:

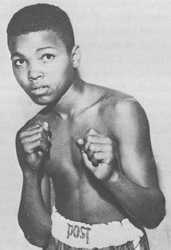

True Strength in a Man

with

a discussion about Muhammad Ali

By Michael Palmer

Aesthetic

Realism shows that true strength in a man is

our desire, our need, to have

good will for the world and people. In

issue 121 of The Right

of Aesthetic Realism to Be Known,

titled "Good Will Is Aesthetics,"

Eli Siegel writes:

Good will can

be described as the desire to have

something else stronger and more

beautiful,

for this desire makes oneself stronger and

more beautiful.

Studying what

good will is, and having it as a conscious

purpose, has made

for big changes in my life. I have deep

feeling for people that I

never had before. And I learned about

the thing in myself and in

every person that most weakens our lives — it

is contempt, the desire to

despise the world, be superior to it.

This is the thing that makes

us feel our life is a failure.

Aesthetic

Realism

Explained that I Had Two Ideas of

Strength

Growing

up in the Bronx,

New York, I wanted to become a

sportscaster. I hoped to be able to

thrill people with descriptions of action on

the playing field. I was also

a very competitive person who, while

appearing friendly, inwardly hoped

that people would flop. When I started

working as a desk assistant

at WCBS Radio, I was angry that a colleague,

who had a similar job, was

trying to advance and might do so ahead of

me. I secretly tried to

undermine him, indirectly letting the boss

know that he was often on the

phone looking for a better job. When

he eventually got fired, I was

glad but also so ashamed that when I'd meet

him after that, I was unable

to look him in the eye. I felt beating

out other people was how I'd

be strong, but I knew I was dishonest.

In

a class I attended in 1972, Mr. Siegel spoke

to me about why I felt

so bad and I felt understood. He

asked:

Do you think

there is something that impels one to hope

one has had a good effect?

Is there an imperative there? Do you

think you would feel bad if

you felt you had a bad effect on anyone?

"Yes,"

I replied, and Mr.

Siegel continued:

Do you like

to encourage people? Do you think if

you failed to encourage people

you would feel bad? The chief thing

we are concerned with is what

we might have done that we didn't

do. Ethics consists of what might

be, what is permitted to be, and what

needs to be. There is an imperative

to think as well of ourselves as we can.

I

thank Mr. Siegel for showing me that what

will have us think well of

ourselves is having good will, wanting other

people to be strong.

Muhammad

Ali

and True Strength

I

believe the desire to

have good will was impelling former

heavyweight boxing champion Muhammad

Ali in 1967 when he spoke out passionately

against the brutal injustice

of the U.S. in the Vietnam War. His

feeling for the people of Vietnam

who were being killed by American bombs and

guns and the courageous stand

he took — refusing to be drafted — was a

beautiful example of strength

in a man; and while it resulted horribly in

his being banned from boxing

for nearly four years, it made for

self-respect in Ali and admiration of

him by people all over the world.

Muhammad

Ali was born Cassius Marcellus Clay in

Louisville, Kentucky in

1942, named after an abolitionist of the

19th century. His father,

Cassius Clay Sr., worked as a painter of

billboards and murals and spoke

out often at home about the fight for civil

rights in America. His mother,

Odessa Clay, worked cleaning homes in the

white, affluent part of the city.

In his autobiography, The Greatest, My

Own Story, written with Richard

Durham, Ali says:

As early as

I can remember I noticed the difference in

the way black and white people

lived. Louisville was a segregated,

racist town; the smell of the

old Slave South hung as heavy as the smell

of famous whiskey and horses.

In

1956 the vicious murder in Mississippi of

Emmett Till, a young African-

American, affected Ali greatly. Till,

only 14, the same age as Ali,

was killed by a mob of whites. Seeing the

newspaper accounts enraged the

young Cassius Clay, and he felt he had to

get back at white people for

Till's death. Days later, he and a

friend vandalized railroad tracks

near his home, causing a derailment.

Fortunately no one was hurt.

But as Aesthetic Realism shows, anger, if it

is just, is also accurate

— in behalf of the world and people.

Ali came to feel the way he

showed his anger here was not accurate, and

for years he said he felt ashamed

of this occurrence.

Meanwhile,

the young man was also becoming interested

in boxing. The first time he

was in a boxing gym at the age of 12, he was

captivated.

In

an Aesthetic Realism lecture of April 1965,

Mr. Siegel spoke about why

people are affected by boxing when he

discussed an essay by the 19th century

English critic William Hazlitt, titled "The

Fight," about an 1821 boxing

match. Mr. Siegel said that

Hazlitt, in describing the match,

was giving external form to fights he felt

in himself, including the fight

between arrogance and modesty, simplicity

and trickery. Mr.

Siegel explained:

"We

are

looking for a good fight because if there

isn't a good fight which

makes for a conclusion, things in us will

be annoying each other perpetually.

There are two phases of conflict. One is

the possibility that conflict

changes into a fight which shows something

has a likable result. The other

is that conflict go on like a tired worm

on a hot day dragging itself across

Fifth Avenue. It's very unlikable, and if

conflicts are not solved, they

grow weary. A weary conflict is one

you don't know you have." "We

are

looking for a good fight because if there

isn't a good fight which

makes for a conclusion, things in us will

be annoying each other perpetually.

There are two phases of conflict. One is

the possibility that conflict

changes into a fight which shows something

has a likable result. The other

is that conflict go on like a tired worm

on a hot day dragging itself across

Fifth Avenue. It's very unlikable, and if

conflicts are not solved, they

grow weary. A weary conflict is one

you don't know you have."

I

wish Muhammad Ali could have heard this —

that the conflict in him, which

is in every person, between liking the world

honestly and finding reasons

to have contempt for it, could be in the

open as in a boxing ring, could

be understood, and have "a likable result."

©

2014 Michael Palmer

|